Referencing commits

There are many ways to get to a commit.

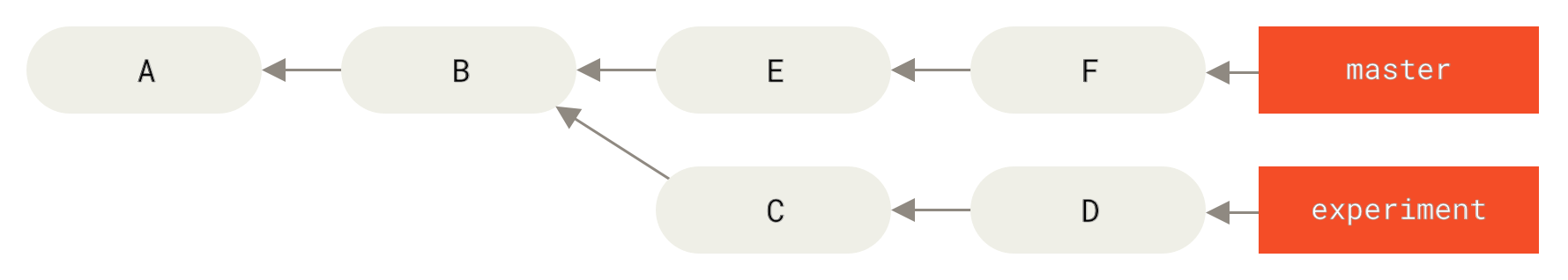

master^ # E (parent commit)

master~3 # A (third ancestor)

C^^ # A (parent of parent)

B~1 # A (parent)

^B # everything except A and Bparents vs ancestors

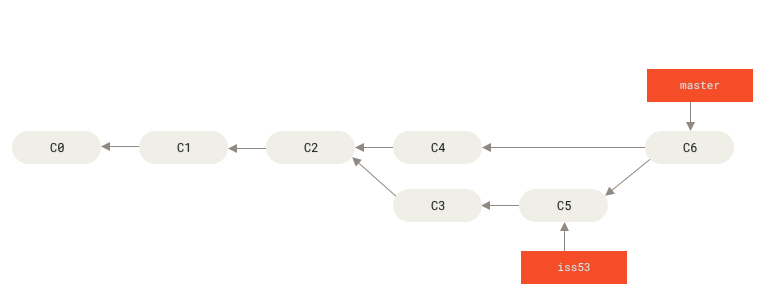

master^ # C4 -- first parent of a merge commit

master^2 # C5 -- second parent of a merge commit

iss53~2 # C2 -- second ancestor (the parent of the parent)

master^2~1 # C3 -- the parent of the second parentReflog

Use reflog to see the “move history” of a given ref (branch or HEAD).

I.e. what commits did the given ref point to in time (as opposed to what is the lineage of given commit).

# assumes HEAD by default

git reflog

# or given a specific ref

git reflog master

# same as

git log -g masterThis adds yet another way to reference commits:

# which commit did master point to 3 moves ago

master@{3}

# which commit did HEAD point to 5 days ago

# i.e. what was I working on 5 days ago?

HEAD@{5.days.ago}Blame

blame allow us to understand who and when made changes.

# display which commit last changed each line of my-file

git blame my-file

# limit the output to specific line range

git blame -L 5,10 my-file

# display changes to a my-file commit by commit

git log -p -- my-fileSigning commits

While git requires the user to provide basic identity information (name, email), by default git does NOT guarantee that commit author is who they say they are.

For projects that require extra security, each commit can be signed.

This is possible by using git in conjunction with gpg and the -S flag:

# create a signed commit using the configured pgp key

git commit -S -m "you can be sure I made this commit"

# displays signature information for each commit

git log --show-signatureWe will not cover the details of how to setup or use gpg keys, but I’ve linked additional resources and guides if you are curious.

Tags

Tags can be used to mark important milestones in a project’s history (such as release versions e.g. v1.0)

Git supports 2 types of tags:

-

Lightweight - very similar to a branch, but cannot be changed

-

Annotated - similar to a signed commit, but holding additional tagging details

Lightweight tags

The main difference between a Lightweight tag and a branch is that tags CANNOT be changed to point to a different commit.

# tag the current commit as v2

git tag v2.0.0

# tag a previous commit in the history

git tag v1.0.0 7ca1be

Annotated tags

Annotated tags create their own object (similar to a commit). They can be signed (like commits). They CANNOT be moved as well.

# create a unsigned annotated tag

# notice annotated tags have their own message

git tag -a v2.3.0 -m "Release v2.3: Blue Kiwi"

# create a signed annotated tag

git tag -a -s v2.5.0 -m "Notes for version 2.5"Manipulating tags

# list all tags (both Lightweight and annotated)

git tag

# list all tags matching pattern

git tag -l v2*

# delete a tag

git tag -d v1.75-tmpTags are NOT shared by default, you have to push them explicitly:

# push all tags to the origin remote

git push origin --tags

# push tag v2.0 to the remote called github

git push github v2.0

# delete a tag on a remote

git push origin --delete v2.0Bisect

Bisect allow us to find which commit introduces a bug (or any specific behaviour we might want to pinpoint).

It uses a binary search to jump around the project history, allowing you mark whether the selected revision

is either good or bad

# start the bisect process with the current commit

git bisect start

# mark the current commit as bad i.e. containing the bug

git bisect bad

# mark a commit as good i.e. not containing the bug

git bisect good 25aef7

# delete the bisect state and return

# to the initial starting commit

git bisect resetBisect will try to choose the minimum number of commits you need to review.

You can use an appropriate command to automatically validate if the commit is good or bad. (e.g. compile the code, run tests or performance benchmarks)

Multiple work-trees

Git allows you to have multiple versions checked-out at the same time:

# creates a branch called bugfix and checks it out

# into a working directory called bugfix

# in the parent of the current directory

git worktree add ../bugfix

# checkout branch origin/broken into a

# separate working directory in your home directory

git worktree add ~/my-project-bugfix origin/broken# list all worktrees

git worktree list

# delete a worktree, needs to be clean

# the corresponding branch is still

# part of the project history

git worktree remove bugfixMultiple histories

Sometimes it might be useful to start a branch that is completely disconnected from the project’s existing history.

This is useful when you want to keep track of a set of related files that change semi-independently from the main-line history of the project (e.g. build artefacts)

# create an orphan branch called deploy

# there are NO commits on this branch

git checkout --orphan deployThe state of the worktree is unchanged, but all files will be untracked.

Use case: deploy branch

After creating a disconnected (orphan) branch, you can

delete or ignore all “regular” project files, committing

only your output / build directory.

By committing these artefacts separately, you avoid needing to resolve conflicts in them when modifying the main-line code.

But also, the artefacts stay versioned and within the same repository.

This was the most popular way of setting up github pages, until the introduction of

Github actions

Use case: cleaner public history

When publishing / open sourcing a project it might not be appropriate to publish the full history of commits.

In these cases an orphan branch can be used to established a “cleaner” history that you can comfortably share on the internet while keeping the full history intact.

You can then push each line to its own remote (public and private).

Submodules

If you put a git repository inside another git repository,

the top-level is called a superproject. The nested repository is called a submodule.

Each repository will have its own independent history. The superproject stores only the sha of currently checkout commit of each submodule.

This is useful when importing the code for a dependency (e.g. a library) and you want to have fine-grained control over which version you want to use.

It is also useful when you want to work on several projects together, but keep their histories separate.

# add an existing repository as a

# submodule of the current repo

git submodule add path/to/other/repo

# clone a repository including all submodules

git clone --recurse submodules