Bare repositories

It is possible to create a git repository WITHOUT checking out a working tree.

The bare repository can be used a shared remote or as a deployment target.

This is especially useful in sever setups where no one will work directly on the instance of the repository.

# create a repository without a working tree

git init --bare

# clone a repository without a working tree

git clone --bare </path/to/repo>If we now ls inside the repository directory, we will find the contents

that usually sits in the .git directory.

Exploring the .git directory

The .git directory is where git stores all its internal state:

- refs (branches, tags, HEAD)

- objects (file blobs, trees, commits)

- hooks (scripts)

- config (remotes, local settings)

What commit is my branch pointing to?

git rev-parse branch-name

# prints the sha of the commit that

# the given branch is pointing to

git rev-parse --short branch-name

# prints a short commit shaCreate a branch by hand

In an existing git repository:

- Get the SHA of the latest commit

cdinto the.git/refs/heads- Create a file named

my-manual-branch - Paste the SHA from step 1. into the file

cdback to the working directory of the repository- List all branches

- Switch to

my-manual-branch

Porcelain vs plumbing

All the commands covered so far are known as porcelain commands -

they are high level - meant to be used directly by end-users in regular situations.

Git exposes another set of low-level commands called plumbing commands.

They are NOT meant to be used for day-to-day management of repositories, but rather allow for fine grain, custom operations.

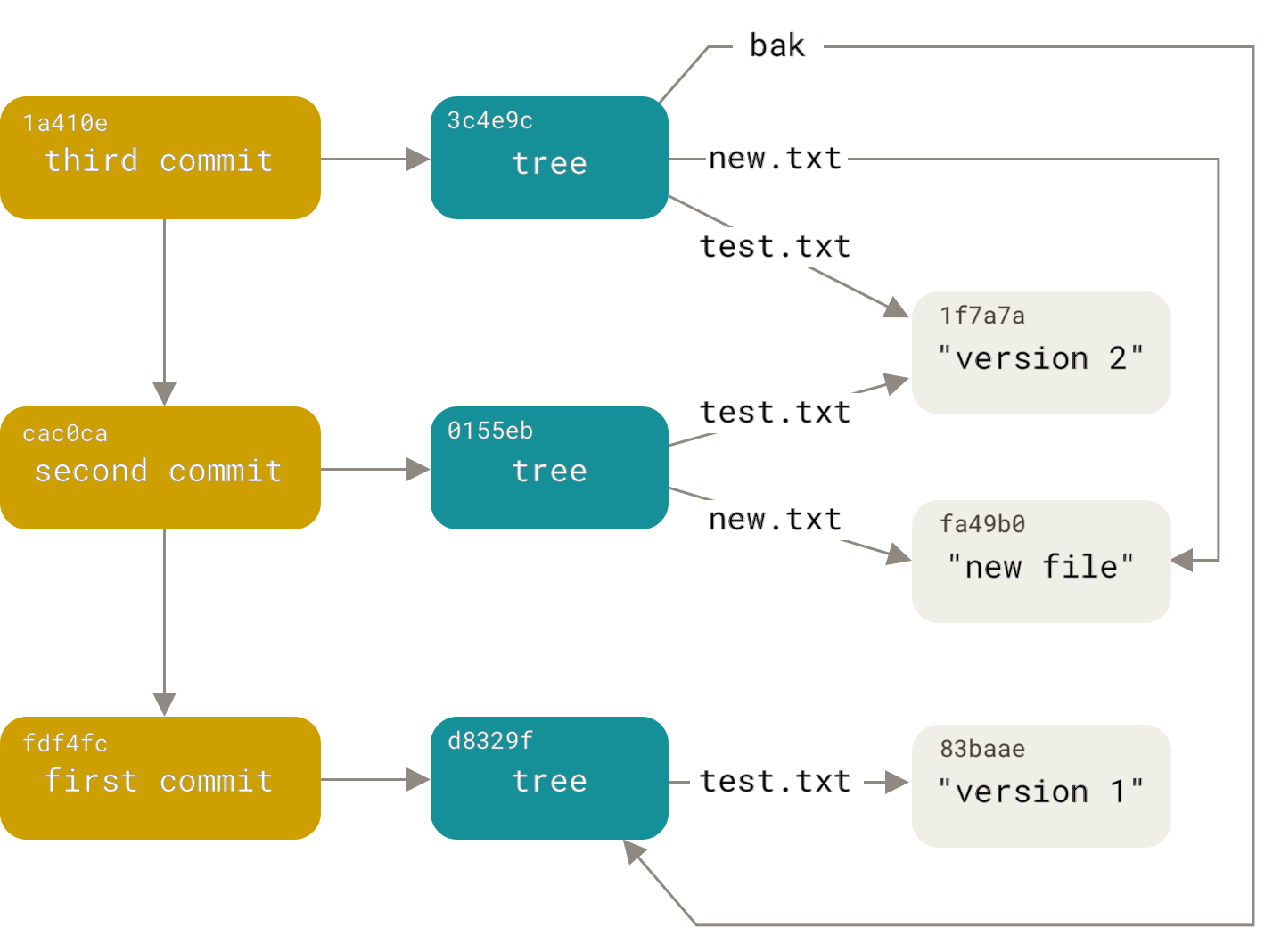

How git stores content

Internally, git does not ‘care’ about files - it stores content.

Content is stored in such a way that the same content will only be stored once.

echo 'super cool code' | git hash-object -w --stdin

# prints out a SHA e.g. f0f23eaf6c63...

The previous command instructed git to store the given string.

We can now find where git stored it in the ‘object database’:

ls -R .git/objects

# prints out .git/objects/f0:

# f23eaf6c63... (same as before)

# try printing the contents of this file

cat ./git/objects/f0/f23eaf6c63...

# prints binary data?!

Viewing content

Use cat-file to view the actual content stored in an object:

# view a blob object by SHA

git cat-file -p f0f23eaf6c63

# prints: super cool code

# view a tree object

git cat-file -p HEAD^{tree}

# view a commit object

git cat-file -p HEAD^{commit}

Optimized for efficiency

Git splits the SHA of objects to allow large repositories to work on file systems with small limits (e.g. 65k file per directory in FAT32)

This also increases efficiency under any file system

Confirm git deduplicates content

- Create 2 files with the same content (e.g. ‘ABCD’)

- Commit both files

- Examine the commit’s tree object

- Compare the SHAs of the files from step 1

- Modify and commit one of the files

- Examine the new commit’s tree object

- Compare the SHAs of the files from step 1

Modifying the staging area

Internally git stores the state of the staging area in the .git/index file.

The update-index command allows us to modify it:

# add content to the staging area

# 100644 indicates normal file

# SHA of blob object

# name for file in the tree

git update-index --add --cacheinfo \

100644 83baae6180... test.txt

# view the state of the staging area

git statusThe write-tree command is used to create tree objects:

# create a tree object capturing the

# current state of the staging area

git write-tree

# prints sha of the newly created tree

# view the newly created tree

git cat-file -p <sha>Manually creating a commit

We can create a commit from any tree object:

# creates a commit

echo 'My commit message' | git commit-tree <tree-sha>

# prints commit sha

# view the commit object

git cat-file -p <commit-sha>

# or view using porcelain commands

git show <commit-sha>in the above example, the newly created commit does NOT have a parent commit

Use the -p <commit-sha> option to specify a parent commit:

echo 'commit message' | git commit-tree \

<tree-sha> -p <parent-commit-sha>Other meta refs

Apart from HEAD, git exposes other useful meta refs:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| FETCH_HEAD | the last branch which you fetched from a remote repository |

| ORIG_HEAD | the position of the HEAD before complex operations, so that you can easily change the tip of the branch back to the state before you ran them |

| MERGE_HEAD | the commit(s) which you are merging into your branch when you run git merge |

| REBASE_HEAD | the commit at which the operation is currently stopped, either because of conflicts or an edit command in an interactive rebase |

There are even more plumbing commands and advanced git features which you can explore in the git manual and book.

As stated in the beginning of this section - these commands are NOT meant to be used on a day-to-day basis. They are useful to understand how git works under the hood.

Git Hooks

Hooks provide a way for you to execute custom programs when important events occur within git.

There are 2 types of hooks:

- Client-side

- Server-side

NOTE: Hooks are NOT copied when cloning a repository - they must be enabled explicitly or installed using an external tool (e.g.

husky)

Client-side hooks

These hooks allow you to customize behaviors when executing local commands.

They can be used to enforce a commit message style, run tests before committing, etc.

Server-side hooks

These hooks can be used in a shared repository to enforce behaviors when receiving pushes.

They can be used to reject unwanted commits, or to trigger actions after the changes have been received.

pre-commit (client-side)

This hook triggers when the user runs git commit

If this hook script exits with a non-zero code, the commit is rejected.

Useful for making sure tests are executed and pass locally.

pre-receive (server-side)

This hooks triggers when a repository is being pushed to. It gets a list of all pushed branches as input.

If this hook script exits with a non-zero code, the commit is rejected.

Useful for enforcing permissions or project policies (e.g. fast-forward updates only).

post-receive (server-side)

This hooks triggers after a repository receives and processes a push. It gets a list of all pushed branches as input.

This hook cannot reject the push.

Useful for restarting a service (web server) or sending notifications (email).

Enforce updates to README file on commit

In an existing repository:

- Create a file

.git/hooks/pre-commit - Execute

chmod +x .git/hooks/pre-commit(this makes the file executable which enables the hook) - Edit the file so that if rejects any commits that do NOT modify the README file

Hints:

git diff --cached --name-onlyprovides a list of all modified files- Use

exit 0for success;exit 1for failure

Solution to class exercise

#!/bin/bash

# Pre-commit hook to ensure README file is modified in every commit

# Check if any README file is being committed

# This checks for common README variations (case-insensitive)

if git diff --cached --name-only | grep -iE '^README(\.(md|txt|rst))?$' > /dev/null; then

echo "✓ README file has been updated"

exit 0

else

echo "✗ Commit rejected: No changes to README file detected"

echo ""

echo "This repository requires all commits to include modifications to the README file."

echo "Please stage changes to your README file before committing."

echo ""

echo "Expected file names: README, README.md, README.txt, or README.rst"

exit 1

fi